I’ve had ideas like this before.

Over the years, there have been plenty of moments where a new technology showed up and people rushed to declare that everything was about to change. Sometimes they were right. Sometimes they were early. Sometimes they were just obnoxious and faded out with the fad.

More than once, I chose not to act.

Not because I couldn’t build something, but because it didn’t feel like the right moment. The pieces weren’t there yet. Or the problem was still being solved well enough by humans. Or the solution would have created as many issues as it fixed.

My dad was a video engineer by trade. He was one of, if not the first, people in Kansas City trained to run a slow-motion reel-to-reel machine. His experiences with new and emerging technologies helped shape how I think about when to get involved, and when to sit on the sidelines.

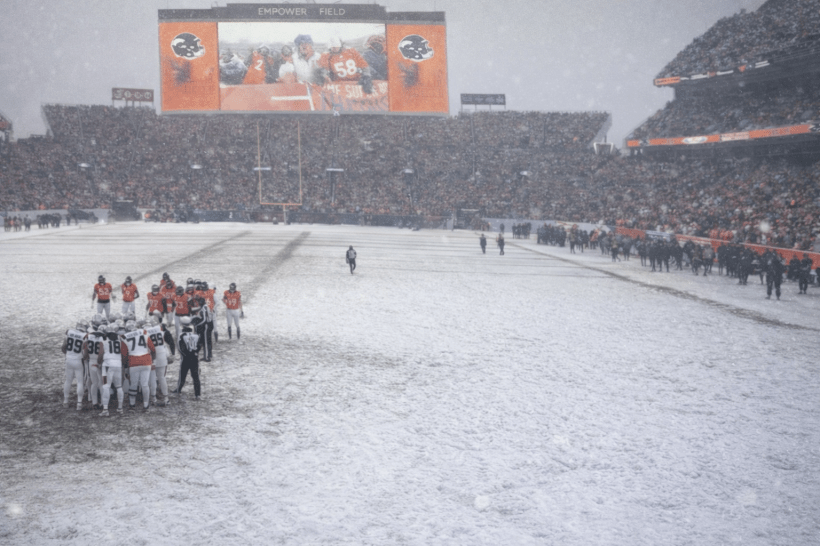

When Chyron video technology began emerging in the 1960s and 1970s, it was used sparingly. My dad wasn’t trained on Chyron yet, but he had an idea. He took a small video camera, mounted it on a tripod, and pointed it at the scoreboard during a baseball game.

Later, he did the same thing for football and other sports.

That simple workaround helped change what viewers came to expect from televised sports. In a nine-inning baseball game, it’s nice to know the inning, the score, and the time at any moment. Today, those elements are permanently embedded on your screen, so normal you don’t even notice them. They’re expected.

My dad saw a technology that wasn’t being used in the best way possible, and he acted at the right moment.

Experience has a way of teaching you when to move. He was right.

It seems like just yesterday

It seems like just yesterday, but I’ve lived through multiple waves of tooling shifts myself. Each one promised to simplify software development. Each one delivered real gains, along with new kinds of friction.

What never really went away was the same underlying problem:

humans doing invisible coordination work between systems that don’t quite understand each other.

We learned to live with it. We staffed around it. We normalized it.

For a long time, that was the right call.

Why This Time Feels Different

What’s changed isn’t just the technology. It’s the combination of things finally lining up, and the growing awareness of the gaps that still need to be filled.

We now have systems that can reason just enough to participate in work, not just execute it. We have workflows that can adapt instead of forcing everything down a single happy path. And we’re finally talking openly about the cost of context switching, glue work, and human babysitting of software.

More importantly, we’ve learned what doesn’t work.

Blind automation doesn’t scale judgment. More tools don’t automatically create clarity. And faster output doesn’t guarantee better outcomes.

Those lessons matter.

Waiting Was Part of the Work

If I’m honest, part of being ready now comes from knowing what I don’t want to build.

I don’t want another system that just moves work faster without understanding it. I don’t want something that replaces human judgment instead of supporting it. And I don’t want to rush something into the world just because the timing feels exciting.

I waited until it felt necessary, not just possible.

Close, But Not Quite There Yet

I’m finally at a point where it feels okay to say that I’m building something. In truth, I have been for months.

I’ll be opening a beta soon. I can’t say exactly when yet. But I’m close enough now that the direction is clear and the product is taking its final shape.

For the first time in a long time, it feels like the right moment to act.