This time of year has a way of slowing things down.

As winter settles in and we all spend a little more time with family and friends, there’s often a moment when the noise quiets just enough to think. For most people, I’m sure it’s about the magic of the holidays, time with family and friends, or maybe even a warm-weather vacation. For me, my head wanders to my work. Not the next sprint or the next feature, but what actually matters over the long haul.

This year, that reflection keeps coming back to a simple question:

What really makes a great engineer?

After decades in this industry, I’ve seen tools change, paradigms shift, and entire job descriptions come and go. But I’ve also watched one critical skill slowly fade into the background.

And right now, that skill matters more than ever.

It Isn’t Coding Speed or Tool Knowledge

The most valuable skill I’ve seen engineers lose isn’t typing speed, language fluency, or familiarity with the latest framework.

It’s not PR velocity or anything measured by DORA metrics. It’s definitely not who has the deepest front-end framework expertise.

All of those things are valuable. But something else is more important.

It’s the ability to reason through ambiguity.

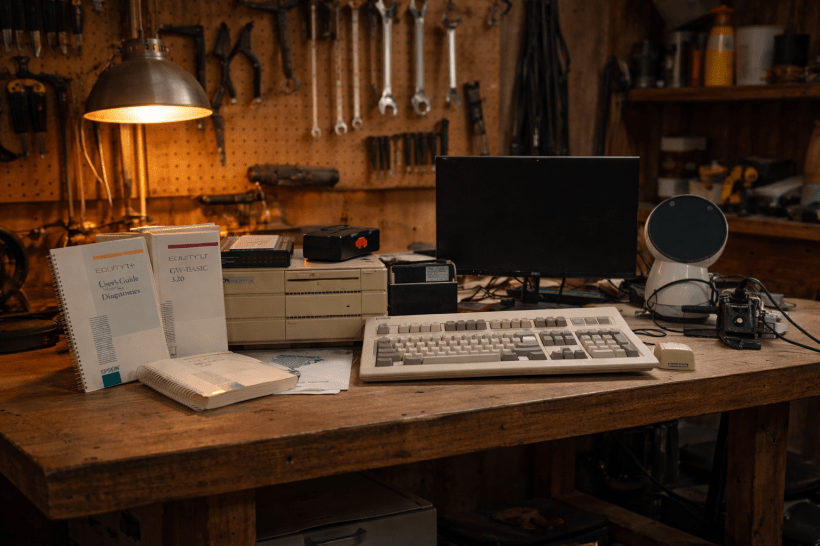

When I was coming up, we didn’t have the luxury of abstraction layers everywhere. If something didn’t work, you traced it. You reasoned about it. You figured out why.

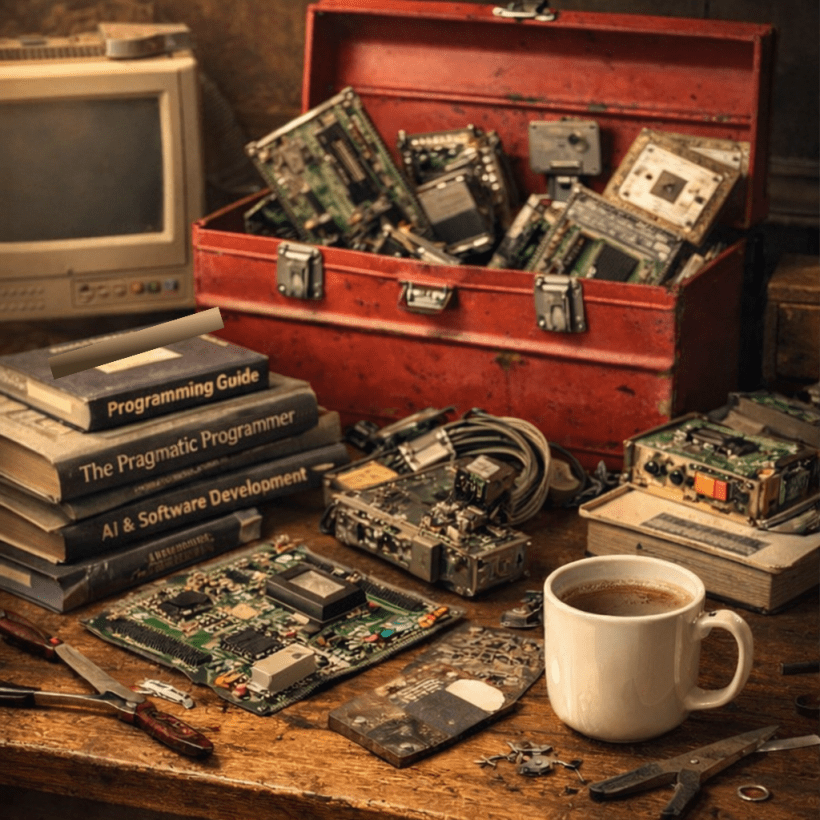

I’ve mentioned before that I used to test on algorithms in my hiring assessments. They mattered. Not because engineers would be implementing them every day, but because algorithms expose reasoning, tradeoffs, and comfort with uncertainty.

The final part of my assessment was a four-question story titled “One Bad Day.” In it, engineers were faced with real-world problems and incomplete information. There were no right or wrong answers. What mattered was how they handled uncertainty when confronted with it.

Those questions revealed how someone thinks when there isn’t a clear path forward.

As software evolved, we got very good at assembling systems. We got much less comfortable sitting with ambiguity.

Abstraction Is Powerful, But It Has a Cost

Modern tools are incredible. They let us build faster and bigger than ever before. But they also hide complexity, and when complexity is hidden long enough, people forget it exists.

That’s how we end up with engineers who are productive, but uneasy the moment something doesn’t behave as expected. When the happy path breaks, the thinking muscle hasn’t been exercised.

AI accelerates this trend if we’re not careful.

Why This Skill Matters More Now, Not Less

There’s a fear that AI will do the thinking for us.

I believe the opposite.

AI is very good at producing output. It’s much worse at knowing when that output is wrong, incomplete, or misaligned with intent. That gap is where human reasoning becomes invaluable.

The real present in this new era isn’t faster code generation. It’s the opportunity to refocus engineers on judgment, evaluation, and problem framing.

Those are learned skills. They compound over time. And they don’t disappear when tools change.

The Gift That Actually Lasts

As you head into the end of the year, maybe while you’re opening presents or just enjoying a quieter moment, this is the thing worth investing in.

The greatest gift you can give yourself as an engineer isn’t another tool or certification. It’s the willingness to slow down, sit with ambiguity, and reason your way through it.

That skill never goes out of style.